Fresh lease of life to privatization process

In a very significant recent development, Torrent Power moved closer to taking over power distribution in the Union Territory of Dadra & Nagar Haveli and Daman & Diu (DDN&DD). The Gujarat-based company, with a significant presence in the entire power value chain, has signed an agreement with the said UT administration to acquire controlling 51 per cent in the JV that will be responsible for power distribution activities in the UT of DNH&DD.

This is a major step forward for the government’s proposal, announced in May 2020, to privatize power distribution in all UTs.

The modality to be followed is the joint venture route where the private sector player will own 51 per cent equity stake (and management control) with the respective UT administration holding the remaining 49 per cent.

If matter progress well, power utility CESC will also take over power distribution in the UT of Chandigarh, on similar lines.

Privatization of power distribution of UTs is inherently different from the earlier attempts at privatization, which largely had to do with the asset-light distribution franchisee model. It must also be borne in mind that attempts at privatization were targeted in areas with high AT&C losses. However, in the case of UTs, the power distribution sector is not loss-making, if not highly profitable. This was precisely why several employee unions opposed the move, leading to some delay in finalizing the process.

The distribution franchisee model has not left a positive impression; there have been more failures and abortive attempts, than successes. What the government is now following is the distribution licensee model through the JV route where the private sector holds 51 per cent equity stake and management control, with the state government or UT administration holding the remaining 49 per cent.

This JV route has been phenomenally successful in Delhi, with Tata Power and Reliance ADAG Group being the private partners in two separate JVs. The recent attempt at similarly privatizing power distribution in Odisha, through four separate JVs with Tata Power, is also showing positive signs.

Power distribution is that area where the revenues for the entire power value chain are ultimately generated. It is also the only customer-facing link in the value chain. This being so, it is best that power distribution, in general, is handled by the private sector. Most state government discoms have a long legacy of commercial inefficiency. It is time that the private steps in.

While privatization needs to be pursued, it is also imperative that the much debated separation of “wire” and “supply” businesses of power distribution is implemented. This will bring more competition amongst private sector players in the “supply” side, which is in the ultimate interest of the end-consumer.

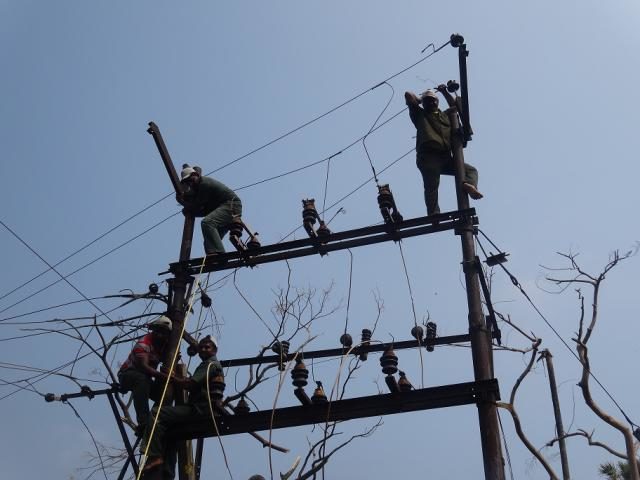

(Featured photograph, sourced from Torrent Power, shows replacement of electricity meters in Bhiwandi before and after Torrent Power took over as the distribution franchisee.)

(The author of this article, Venugopal Pillai, is Editor, T&D India. He may be reached on venugopal.pillai@tndindia.com.)