For quite some time now, Power Grid Corporation of India, the Central PSU engaged in interregional power transmission, has been in the news with respect to separating itself from the “CTU”, which is “Central Transmission Utility.” It is worthwhile to understand the issue in some detail.

Something very significant had taken place on January 5, 2011. The power ministry ruled that all power purchases made after this date would be based on tariff-based competitive bidding (TBCB) mechanism. This has had serious bearing on all aspects of the power value chain—generation, transmission and distribution.

In the context of interregional and interstate power transmission, PGCIL was always the agency “nominated” by the power ministry. PGCIL could build power transmission lines on the “cost-plus” method, which meant that it could quote a project cost, factoring a mark-up on the envisaged construction cost. In other words, PGCIL was always assured of return on investment as the tariffs charged by PGCIL for transmission of power were based on the expenditure incurred on constructing the line.

Power Grid no longer nominated agency

Post January 5, 2011, PGCIL lost its status of being the “nominated agency” for building interregional and interstate lines. Under the TBCB regime, PGCIL would have to compete with private players and win projects based on the tariff quoted. It surely would have been a culture shock for PGCIL. The Central PSU now had to compete with the same private entities that used to be contractors for its projects. These private entities, in turn, were contractors that choose to groom into developers. In other words, a private contractor for PGCIL would now aspire to become an owner and manager of a transmission line—much more than simply building it for PGCIL. The TBCB regime, as one can see, marked the evolution of private enterprise in interregional power transmission. We have today private developers like Sterlite Power, Reliance (ADAG) Group, Kalpataru Power Transmission, etc—all of whom are sharing the power development space with PGCIL.

It is important to note that PGCIL along with being a power transmission company, in the sense of owning and managing interregional transmission lines, is also responsible for grid management and for planning the nationwide transmission infrastructure. For PGCIL to fit fairly into the TBCB regime, other aspects, namely the grid management, and the planning of transmission network, also had to be worked upon.

Grid management hived off, now it is CTU’s turn

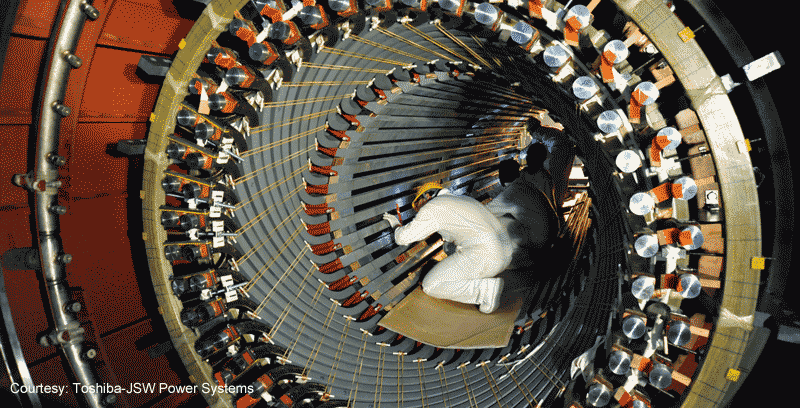

Steps to reorganize PGCIL were taken much before the January 5, 2011. In February 2009, the grid management operations of PGCIL were hived into a separate company called Power Systems Operation Corporation Ltd (POSOCO). When incorporated, it was a wholly-owned subsidiary of PGCIL. The grid management operations of PGCIL, now under POSOCO, include one national load dispatch centre (NLDC), five regional load dispatch centres (RLDC) and 33 state load dispatch centres (SLDC). The incorporation of POSOCO was aimed at ring-fencing the grid management operations from PGCIL, though POSOCO’s ownership was still with PGCIL.

Very recently, an important development took place. On January 2, 2017, the ownership of POSOCO was transferred from PGCIL to the Union power ministry. The complete equity capital of POSOCO, comprising 30.64 million shares of face value Rs.10 each, was transferred to the power ministry for a consideration of Rs.81 crore. This now makes POSOCO a Central PSU, directly under power ministry. At the organizational level, POSOCO is now at par with PGCIL, as well as other Central PSUs under the power ministry. More importantly, POSOCO will have much more financial autonomy allowing it to even raise resources on its own.

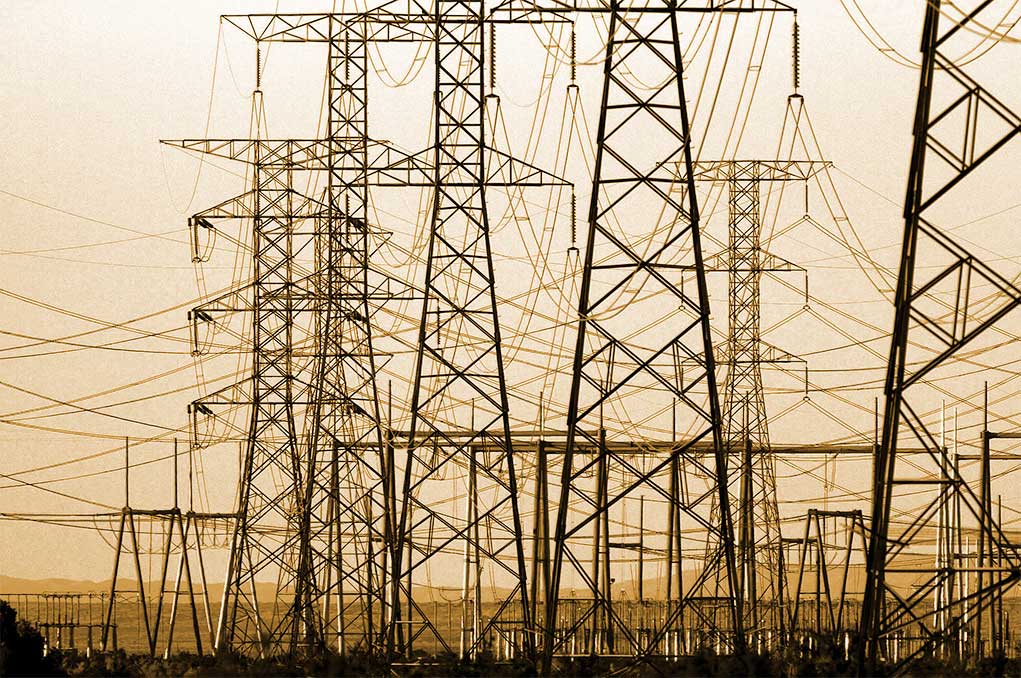

With the grid management issue now taken completely care of, it is time to look at the CTU dimension. Among the various functions of the CTU is that of planning the national transmission network, which essentially means new interregional and interstate transmission systems. The paramount corporate objective of PGCIL is to develop a national grid for the seamless transfer of electricity between the five regional grids—north, northeast, west, east and south. Currently, the interregional transfer capacity of the National Grid is around 62,650 mw, which is very close to the target of 65,000 mw set for end-March 2017, the end of the XII Plan period. It should be remembered that PGCIL does not own this 62,650 mw entirely. Around 10 per cent belongs to private developers, representing projects won by private entities under the TBCB regime.

Also read: The changing complexion of Power Grid Corporation of India

Why the CTU needs to be separated

The CTU is a small but highly specialized cell within PGCIL. It is reliably learnt that the CTU is a group of five or six members. The main job of the CTU is to plan new transmission schemes, to augment capacity of the National Grid. The CTU not only plans new lines, but it also estimates the project cost and other sensitive parameters like the base tariff, etc. All this information is critical whilst bidding out the project under the tariff-based competitive bidding mechanism. Technically, PGCIL has access to this information and this could vitiate the tenets of tariff-based competitive bidding. It threatens to destroy the level-playing field between PGCIL and private developers. This is why the CTU aspect of PGCIL needs to be detached from PGCIL. The power ministry is already working to this effect.

The case of PGCIL is reminiscent of several such instances where Central government undertakings had to be restructured in the wake of the Liberalisation Policy of 1991. One such case is that of the erstwhile Oil & Natural Gas Commission. Till the early part of the 1990s, ONGC was both an operator and a regulator of sorts. When private sector entered the oil exploration business, ONGC could not perform a dual role. Thus, in 1993, was born Oil & Natural Gas Corporation Ltd (a corporate entity under the petroleum ministry) and Directorate of Hydrocarbons (DGH)—the regulator.