India crosses new milestone in EHV equipment testing

National High Power Test Laboratory Pvt Ltd (NHPTL) last week announced that it began commercial operations from July 1, 2017, and that it was now open to accepting enquiries for high-voltage equipment testing. The commissioning of India’s most advanced laboratory for high voltage equipment testing, albeit just the first phase for now, is a very important development for the electrical equipment industry. Not only will the laboratory (located at Bina in Madhya Pradesh) serve Indian customers, it is also expected to attract business from SAARC, ASEAN and Middle East countries.

India’s inadequacy in the field of testing of high- and extra high voltage equipment, typically power transformers, is well known. The new Bina lab is expected to mitigate India’s reliance on foreign testing houses, typically CPRI (Italy) and KEMA (The Netherlands).

India’s two traditional testing laboratories, ERDA and CPRI, have been bolstering their competency but they haven’t really been able to obviate the dependence on foreign labs. For instance, though ERDA is capable of carrying out impulse test on transformers up to 400kV, there is no scope for undertaking the most crucial short-circuit test. The Bina laboratory of NHPTL, on the other hand, is well equipped to carry out short-circuit test on 400kV power transformers. It is estimated that Indian transformer manufacturers spend an estimated Rs.30 crore each year in getting their products type-tested in foreign laboratories. Apart from the high expenses, the turnaround time in getting transformers tested overseas labs is very high.

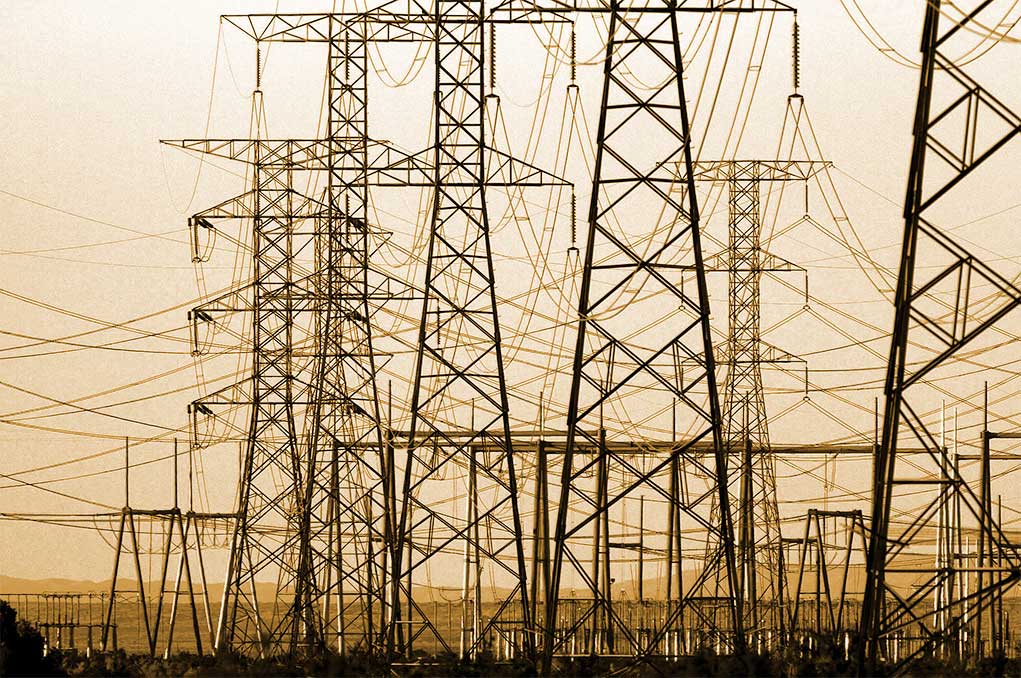

While the first phase of the Bina laboratory is commissioned, it is also encouraging to see that ERDA and CPRI are also moving on with their expansion plans. All this is good news for the Indian power transmission industry that is progressively moving to higher voltages (765kV, 800kV and even 1,200kV). It is also pursuing high voltage direct current (HVDC) power transmission modalities, apart from conventional alternating current (AC).

NHPTL’s Bina laboratory has an intrinsic advantage of having taken birth in a technogically-advanced era. This being the case, it will not face legacy-related impediments of migrating from a low-voltage regime to an extra-high voltage regime. For CPRI and ERDA, on the other hand, this transition will not be seamless. Also, NHTPL is a corporate entity (company) that makes matters like decision-making and fund raising relatively easier than in the case of ERDA and CPRI that are registered as non-corporate entities.

All said and done, India’s reliance on foreign laboratories will decline only gradually. It must be acknowledged that KEMA and CESI, in particular, have been longstanding partners to the Indian electrical equipment fraternity. Certification from these agencies has been very helpful for Indian companies, especially those exporting high-voltage equipment. Both these agencies have played a critical role in the development of NHPTL’s Bina laboratory, right from the conception stage.

Coming back to the Bina laboratory, NHPTL, in the second phase, has envisaged a high power synthetic (HPS) lab for short circuit testing of circuit breakers up to 550kV, 63kA with synthetic methods. Also part of the second phase, is a high current low voltage (HCLV) lab for testing high current withstand capability of electrical equipment such as low-voltage bus bar, contacts, breakers, disconnectors, bushings, current transformers, etc.

Self-sufficiency in high-voltage electrical equipment testing was a cherished dream of Indian electrical equipment manufacturers, and NHPTL’s Bina lab is a definitive first step towards the realization of this dream.