Intrastate transmission needs TBCB boost

Very recently, Power Grid Corporation of India Ltd (PGCIL) completed an intrastate scheme in Madhya Pradesh that it had won under the TBCB modality. In most likelihood, for Madhya Pradesh, this is the first or amongst the early transmission schemes developed using the TBCB philosophy.

PGCIL, the Central power transmission PSU, is already very active in the TBCB-based interregional/interstate power transmission landscape. That PGCIL is also taking keen interest in the intrastate network is a favourable augury to the state-level power grid, in general. PGCIL currently has three intrastate schemes — two in UP and one in MP. It plans to participate in more schemes in these and other states, as and when they come up for bidding.

The disconcerting point however is that not many states are coming forward in adopting the TBCB culture. Even progressive states – Maharashtra and Gujarat to name just two – have not featured the TBCB modality in their transmission network upgrade plans.

The TBCB intrastate transmission scheme that PGCIL recently completed in Madhya Pradesh (Bhind-Guna transmission project) had attracted big names. In fact, all the leading transmission developers showed interest. The e-reverse auction saw as many as 52 rounds, demonstrating the aggression that potential developers evinced. All this goes to prove that there is developer interest but there is a very limited project shelf currently available.

TBCB-based interregional transmission schemes are progressing quite well. PGCIL along with leading private developers like Sterlite Power and Adani Transmission are making useful contributions in enhancing this network, which ultimately adds to the National Grid capacity.

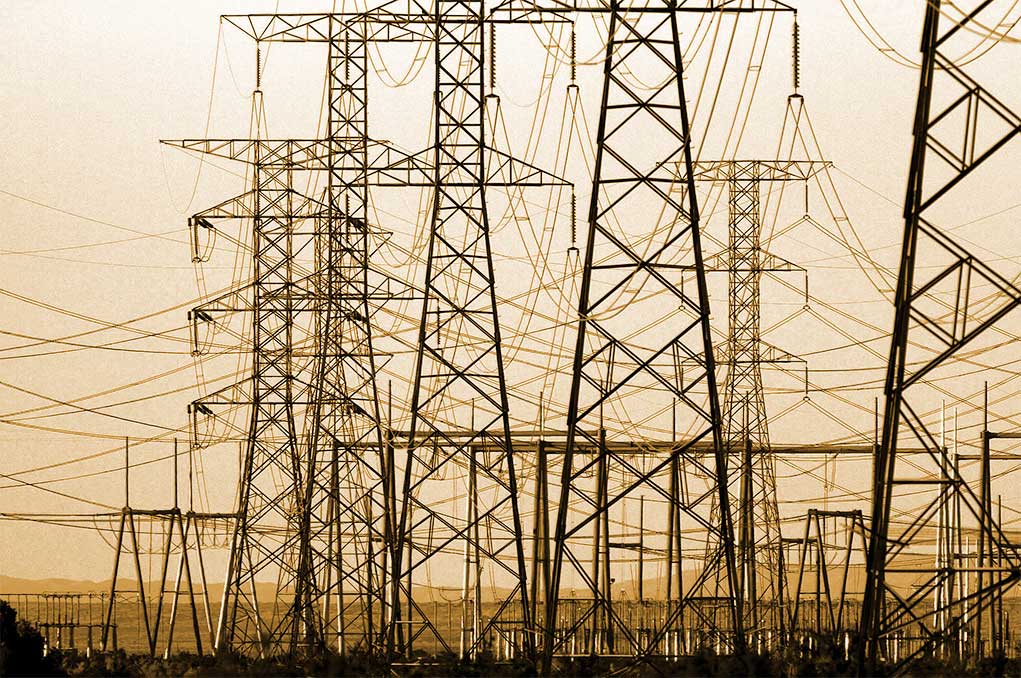

For electricity to reach the end-consumer, it is very important that intrastate grids are also developed concurrently. State power transmission utilities must appreciate that the TBCB route gives ample scope for induction of technology and managerial expertise, apart from project finance. These utilities can be assured of projects completed within the time and cost estimates. Uttar Pradesh, it may be recalled, had invoked the TBCB modality for developing an intrastate transmission scheme, involving 765kV lines, over a decade ago.

Meanwhile, under the Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme (RDSS), private entrepreneurs have a solid opportunity to contribute to upgrading the power distribution network, mainly through smart meter deployment. It is widely expected that the private sector will play a very important role in this Rs.3-trillion RDSS venture.

While power distribution is indeed the weakest link in the power value chain, power transmission is not much better off. The private sector can definitely play an important role if given the opportunity.

State transmission utilities will therefore stand to benefit if they open up a platform for seasoned transmission developers. And what platform could be better than TBCB?

(The author of this article, Venugopal Pillai, is Editor, T&D India. He may be reached on venugopal.pillai@tndindia.com.)